Key Message

Older adults living in Ontario’s long-term care (LTC) homes have experienced some of the most devastating impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, including disproportionate deaths, prolonged isolation from family and essential caregivers and reduced quality of life. In response, national and provincial associations and organizations have launched inquiries, issued expert reports, and offered recommendations. This brief summarizes and consolidates key recommendations from five reports and identifies opportunities to strengthen and integrate these recommendations into the Ontario policy environment.

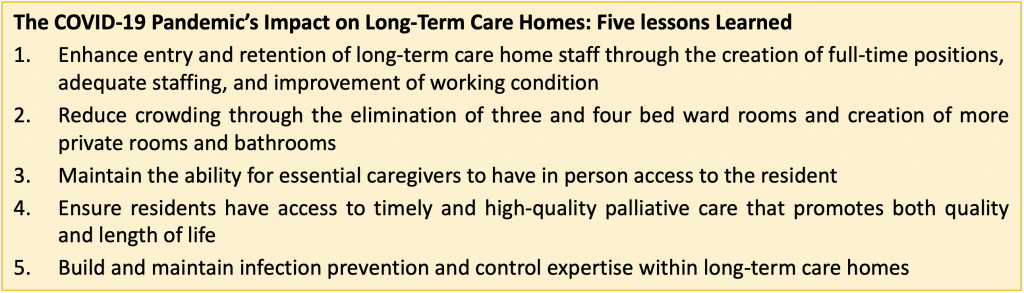

We identified five critical lessons learned:

1) Enhance the entry and retention of LTC home staff through the creation of more full-time positions, adequate staffing levels, and improvement of working conditions,

2) Reduce crowding through the elimination of three and four bed ward rooms and creation of more private rooms with dedicated bathrooms,

3) Maintain the ability for essential caregivers to have in-person access to the resident,

4) Ensure residents have access to timely and high-quality palliative care that promotes both quality and length of life, and

5) Build and maintain infection prevention and control (IPAC) expertise within LTC homes.

These five lessons learned offer opportunities for significant improvement for Ontario’s LTC homes and can optimize safety, quality of life and outcomes for residents and improve the LTC home environment for staff and essential caregivers.

Summary

Background

Many inquiries, reports, and legislative reforms have been released in response to multiple waves of the COVID-19 pandemic nationally and provincially. The volume of analysis of the impact of COVID-19 on LTC presents a challenge to decision-makers to identify and prioritize key areas for improvement and action. This brief consolidates recommendations and offers evidence-supported lessons learned and opportunities for change.

Questions

What are the Federal and Ontario reports that address the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in LTC that align with five key recommendations of focus: enhancing staffing, reducing crowding, ensuring connections, incorporating palliative care and optimizing IPAC?

How could these recommendations be strengthened to guide care for LTC home residents?

What have we learned from the COVID-19 pandemic’s impact on care in LTC homes?

Findings

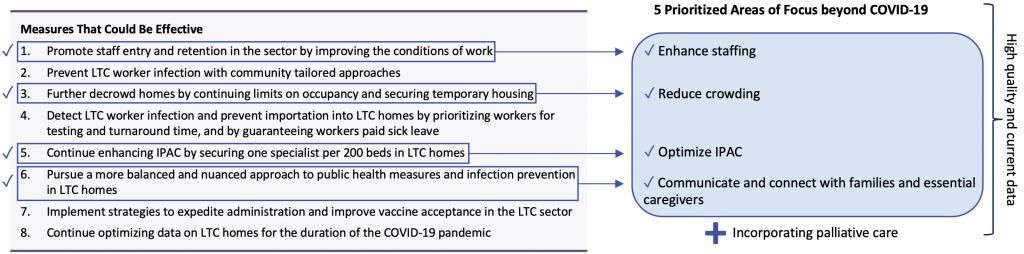

From these reports, we summarized key recommendations in five areas of focus: enhancing staffing, reducing crowding, ensuring connections among residents, friends, their families, and essential caregivers, incorporating palliative care and optimizing IPAC. These five areas were derived from a list of eight measures that were identified as potentially being effective in preventing COVID-19 outbreaks, hospitalizations, and deaths in Ontario LTC homes that were published in an earlier Science Advisory Table brief “COVID-19 and Ontario’s Long-Term Care Homes”. Focusing on areas identified as being of continued importance beyond the COVID-19 pandemic, recommendations in each were synthesized, strengthened and enhanced by leveraging data from Ontario and identifying policy opportunities.

Interpretation

Many lessons have been learned through the devastation that the COVID-19 pandemic caused in LTC homes that should be used as the guiding principle for driving sustained change. Care for residents of LTC homes needs to be reformed and reimagined with the core theme of providing care that is person-centered and delivers the best quality of life for residents. Building on the lessons learned during the is pandemic in each of the five identified areas of focus (enhancing staffing, reducing crowding, ensuring connections, incorporating palliative care and optimizing IPAC) is critical to creating sustained and meaningful change. Having high-quality and current data is important across all five areas of focus. Decision-makers can improve the quality of care for residents in LTC homes by enhancing existing directives, standards, and legislation.

Full Text

Background

The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed systemic problems within the LTC sector that provide the burning platform for change and immediate attention from policymakers. As of March 2022, close to 71,000 Ontarians live in 626 LTC homes. An estimated two-thirds1 of these residents are women and almost 70% have dementia.2 LTC home residents accounted for more than 60%3 of all COVID-19-related deaths in Ontario early in the pandemic, despite residents accounting for less than 1% of the provinces’ older population.4 In response, a series of inquiries have been launched and urgent reports created since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in Canada, providing extensive and varying lists of recommendations.

The quality of care provided in some LTC homes has been an area of concern for many years. More than 80 reports have been published in Canada alone in the decade prior to the COVID-19 pandemic.5 These reports identified gaps, opportunities and recommendations on how quality of care in LTC homes could be improved. The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020 and the resulting devastation experienced by LTC home residents have made these stark gaps in quality of care, all the more visible, highlighting the urgent need for action to improve care. There is a need to identify and prioritize key areas of improvement.

Questions

What are the Federal and Ontario reports that address the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in LTC that align with five key recommendations of focus: enhancing staffing, reducing crowding, ensuring connections, incorporating palliative care, and optimizing IPAC?

How could these recommendations be strengthened to guide care for LTC home residents?

What have we learned from the COVID-19 pandemic’s impact on care in LTC homes?

Findings

The five reports on COVID-19 and LTC homes included in this brief total over 700 pages and include hundreds of recommendations.

Evidence combined with expert opinion is required to make the volume of information in key areas accessible for decision-makers, identify opportunities to implement recommendations using LTC home legislation and policy, and to focus attention on the five key lessons the COVID-19 pandemic taught us about LTC homes.

Our five areas of focus were derived from a list of eight measures that were identified as potentially being effective in preventing COVID-19 outbreaks, hospitalization, and deaths in Ontario LTC homes published in an earlier Science Advisory Table brief “COVID-19 and Ontario’s Long-Term Care Homes”.3 Four were chosen from this list and identified by experts as being of continued importance beyond the COVID-19 pandemic. As such, the items with utility limited to the COVID-19 pandemic and vaccine-related measures were excluded. The fifth area of focus “incorporating palliative care” was included because of its importance to quality of care for LTC home residents. This was highlighted by the exceptionally high death rates of LTC home residents during the pandemic. Having high-quality and current data is an overarching theme across all five areas of focus (Figure 1).

Five priority areas of focus for LTC homes beyond COVID-19, informed by the eight measures identified as potentially being effective in preventing COVID-19 outbreaks, hospitalization, and deaths in Ontario LTC homes published in the Science Advisory Table brief “COVID-19 and Ontario’s Long-Term Care Homes”.

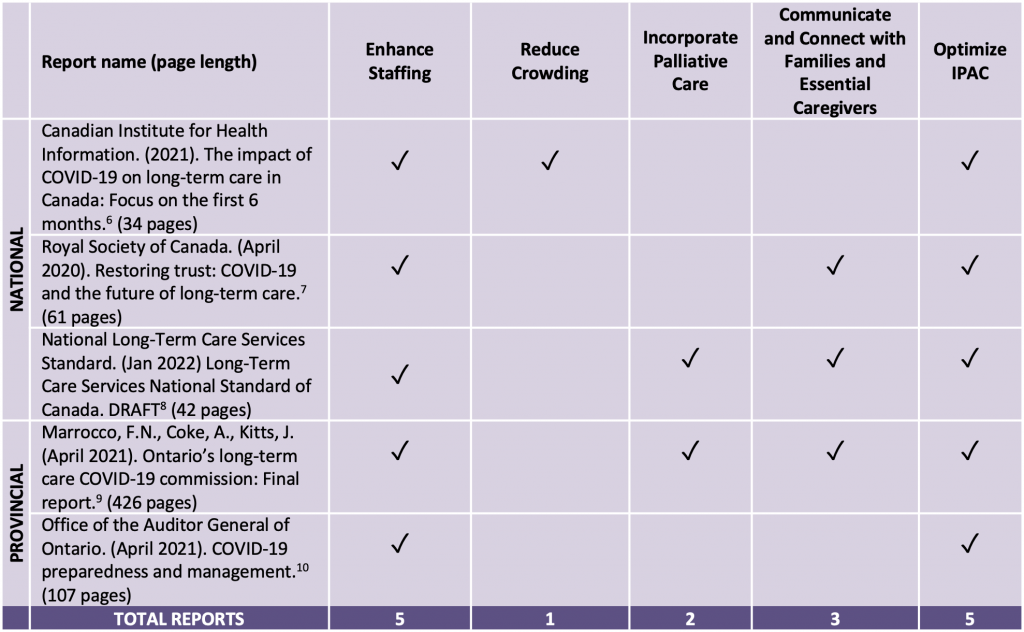

Each of these five reports was reviewed to identify key recommendations to improve quality of care in LTC homes in the five priority areas. Recommendations designed to enhance staffing and to optimize IPAC were included in all of the reports. Three reports provided recommendations to ensure ongoing communication and connection among families, essential caregivers and LTC home residents. Two reports included incorporating palliative care and although there is evidence to show that crowding is a critical factor in infection spread, only one report provided a recommendation designed to reduce crowding or to incorporate palliative care (see Table 1).

Recommendations to Enhance Quality of Care in Ontario Long-Term Care Homes

Recommendations can be strengthened and enhanced by leveraging data from Ontario and by identifying opportunities to link them to policy. The following section describes opportunities for strengthening recommendations in the five areas of focus.

Enhance Staffing

There are nearly 200 mentions of staffing in the Ontario Long-Term Care Commission report alone,9 making it one of the foremost areas to address. Key issues were related to limited staff numbers, turnover, part-time and multi-site employment, low wages, and need for training, among others. This is not the first time these issues have been cited.11–13 Improving conditions of work, creating more full-time positions with better pay and benefits, reducing the use of agency nurses, increasing on-site education have all been recommended as solutions to the shortages and high turnover in the workforce. Years of reports and commissions calling attention to the same staffing issues have had little impact.

Accurate and complete data are critical to the development of strategies for addressing these issues. An advisory group conducted the Long-Term Care Staffing Study for the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care.14 This study generated five key recommendations to address staffing issues. Specifically, staffing levels need to be increased, working conditions substantially improved, along with enhanced training and opportunities for learning and growth. The culture needs to move away from a focus on tasks to quality of life, a move that requires effective leadership. These recommendations are even more important now given the experience with COVID-19. In the response to this pivotal study, the government committed to a minimum of four hours of combined direct care by 2025 by personal support workers, registered practical nurses, and registered nurses as a way to address some of the staffing issues brought to light by the pandemic.15 To adequately assess progress toward this goal, accurate and complete verifiable data are critical. Currently, data on staffing hours are inconsistent, dependent on the source and are presented as averages that are inadequate for identifying problem homes, limiting the utility of this information.14 The US Affordable Care Legislation provides a model for data collection that can provide accurate data in a more efficient,16 timely and cost-efficient manner using payroll-based journal staffing measures.17 The legislation requires each facility to report on the number of nurse and other professional staff in the home to Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services (CMS). This reporting must be done online and on a quarterly basis, providing data for every single day. This allows the public to see the daily nurse staffing levels including on weekends and holidays.17Providing transparency ensures that the mandated level of staffing are provided to promote quality care.

Data collection focused on personal support workers and registered nurses misses a large proportion of the LTC sector workforce, all of whom provide critical care services and should not be overlooked. For instance, security and maintenance workers, laundry, kitchen, and housekeeping staff, among others all enter the LTC home on a regular basis. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the role of all staff in introducing and transmitting infection came under scrutiny. Knowing who moves in and out of a care home is critical for safety and quality. Therefore, data collection needs to be inclusive of all LTC home staff. In addition, we need better ways of tracking the other factors beyond staffing numbers that contribute to the long-standing and current labor shortages in LTC homes including, but not limited to, turnover, injury, and illness rates, temporary, part-time and agency employment, scheduling, and opportunities for advancement. In the most comprehensive nursing home reform since The Nursing Home Reform Act of 1987, a number of reforms are proposed including guidance related to minimum staffing requirements.18 To effectively control infection spread, improve quality of care, and ensure a labor force for nursing homes, we need better and more comprehensive verifiable data that is publicly available so that the government can monitor and be held accountable for progress and improvements in quality.

Reduce Crowding

Crowding and design remain important and under-recognized issues impacting respiratory virus transmission in LTC homes. Of the reports evaluated, only the CIHI report identified crowding as an issue. Data obtained at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic (March 2020) suggest that almost half of Ontario’s LTC homes (at that time housing approximately 77,000 residents) were older design homes.3 Older LTC homes in Ontario have a mix of one, two, and four bed rooms, while newer homes (that largely meet Ontario LTC design standards in place since 2015) have a mix of one and two bed rooms. The number of residents has since decreased to about 71,000 residents (March 2022), primarily due to temporarily capping ward rooms in older homes to two residents and not refilling the vacated beds. In some cases, these LTC homes had three or four residents sharing a single room (and/or single bathroom).19,20 SARS-CoV-2 infection and associated mortalitywere about 50% lower in less crowded homes compared to highly crowded homes.19 In the nursing home reforms proposed in the United States, shared rooms have been identified as a risk for contracting infections and multi-bed rooms will be phased out to provide private rooms.18

Beyond crowding within bedrooms, there are additional factors relating to design that could help prevent the burden of future SARS-CoV-2 waves and respiratory infections, including high-quality heating, ventilation and air conditioning (HVAC) systems, particularly in common areas. Further, increasing the size of shared spaces in LTC homes (e.g., corridors, activity rooms, dining rooms, nursing stations, staff break rooms) could also help reduce transmission risk.

The finding that crowding was associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection and death led to the addition of occupancy limits in Directive 3 for LTC homes.21 Occupancy limits outlined in Directive 3 instructed LTC homes to place all new residents in single or two-bed rooms, with the purpose of reducing the number of residents in rooms occupied by more than two residents. When ward beds were vacated, they were not to be filled unless the room was occupied by less than two residents. This Directive was put in place as a temporary pandemic measure in part to reduce crowding in LTC homes and limit SARS-CoV-2 transmission.21

The LTC home experience with the COVID-19 pandemic along with pre-pandemic respiratory outbreaks, indicate that crowded homes had a greater burden of infections. Older homes have beds that do not meet the Ontario LTC design standards outlined in the LTC Home Design Manual (2015).22 In existing older LTC homes, evidence supports the maintenance of a room occupancy cap of two residents in order to reduce the substantial burden that future SARS-CoV-2 waves have on LTC home residents. A further concern is that single-bed rooms with dedicated bathrooms are not the standard outlined in the LTC Design Manual of 2015,22which still guides the design requirements for new LTC homes built across Ontario. In order to minimize burden of respiratory infections in the future, for new LTC homes, all rooms should be single-bed rooms with dedicated bathrooms unless there is an identified need (e.g., accommodation for couples) for two-bed rooms.

Ensuring Connections among Residents, Friends, their Families and Essential Caregivers

Essential caregivers and family members are critical in maintaining the health and well-being of LTC home residents. In addition to providing the social connections that are so important to the health and well-being of residents, they assist with multiple tasks that support residents and provide important information to both residents and staff.23 The visiting restrictions placed on family members and friends, and other essential caregivers due to COVID-19 have had a serious impact on residents. Harms have not only been to mental health, isolated residents who did not have contact with family or friends were at a greater risk of death.24

Savage and colleagues, using data from Ontario on LTC homes explored excess mortality among LTC home residents who had personal contact with family and friends during COVID-19 compared to those who did not.24Using data from the Resident Assessment Instrument Minimum Dataset, they found that 2.3% (representing 1,550 of Ontario’s 67,589 residents) had no personal contact with family or friends. During the pandemic, LTC home residents without personal contact with family or friends experienced 34.8% greater excess mortality than those who had contact with family or friends (includes phone calls or virtual visits).24 This study is one of the few to examine the impact of isolation within LTC homes and underlines the importance of having family and friends to advocate for residents and provide them with care and emotional support while balancing the risk of COVID-19 introduction into the home through visitors. Management protocols for COVID and non-COVID outbreaks in LTC homes should be reviewed to ensure that limitations on essential caregiver entry and in-home activity are evidence-based, minimized and communicated whenever possible. In extenuating circumstances when in-person visits are impossible, creative alternative solutions to maintaining the ability for residents to have social connection with their family, friends and essential caregivers is critical for their health and well-being.

Incorporate Palliative Care

LTC home residents are frail, and one in four die in the first year after admission,25 yet only two reports mentioned palliative care. The median life expectancy of a LTC home resident is 18 months after entry.26 As such, it is important to recognize that many residents have goals of care that emphasizes quality over length of life; IPAC measures should consider this balance. LTC homes should be prepared to provide palliative care when needed.

There is variation in access to palliative care across Ontario LTC homes. As a result, many residents are transferred to acute care when they are close to death as LTC homes and staff may lack resources and skills to care for seriously ill and dying residents.26 For example, using data from Ontario, Tanuseputro and colleagues found variation in the rate of prescribing of subcutaneous medications for end-of-life symptoms – a general standard of care to support residents who have lost the ability to swallow medications by mouth. They found that the top 20% of homes in terms of prescription volume per capita (about 125 homes) prescribed one of these medications to 82.9% of decedents who died in their homes compared to a rate of 37.6% for the bottom 20% of homes (Tanuseputro P, personal communication).

The highest prescribing LTC homes also transferred residents to die outside of the home at a lower rate than the lowest prescribing homes (12.4% versus 30.0%) (Tanuseputro P, personal communication). These results demonstrate that some homes could use additional support to optimize the quality of the end-of-life period for all residents. Regardless of COVID-19 status, end-of-life care within each home should be prioritized, and that those nearing the end of life should be provided the ideal balance of care geared towards quality and quantity of life. Personal support workers and health care aides require training to improve skills in palliative care, such as the Learning Essential Approaches to Palliative Care (LEAP) courses.27

Strengthen Infection Prevention and Control

All of the federal and provincial reports evaluated included the need to enhance IPAC measures in LTC homes, making this an essential issue for improving the quality of care in LTC. While improving IPAC can be done directly, it is important to recognize that improving staffing, reducing crowding, and finding ways to educate visitors and essential caregivers on visiting safely in LTC homes all also contribute to improving IPAC. There have been major deficiencies identified in IPAC practices observed in LTC homes such as a long-standing lack of basic IPAC techniques in LTC homes. A consistent recommendation from the reports is for a dedicated IPAC specialist within each LTC home. Ontario’s LTC COVID-19 Commission’s final report recommends that the current regulation be amended to require one full-time dedicated IPAC practitioner, per 120 beds to ensure that homes have meaningful access to IPAC expertise. Continuing to strengthen external IPAC partnerships and support available for LTC homes (e.g., IPAC Hubs, local public health, Public Health Ontario) is also needed to ensure timely and efficient support for any IPAC-related challenges.9

Other recommendations in this brief related to staffing and reducing crowding will also improve IPAC. For example, IPAC is facilitated by having full time staff working in one home, minimizing risk of importing communicable diseases between LTC homes, less crowded homes where residents have private rooms and dedicated bathrooms, minimizing risk of spread of communicable diseases. Further, providing essential caregivers and family members with standardized IPAC education to ensure their ability to visit safely and promote their ongoing involvement is critical to ensuring quality of life and optimal end of life care. The recent Ontario COVID-19 Science Table Supporting Long-term Care Home Residents during Omicron slide deck provides helpful guidance.28

The evolving landscape of the COVID-19 pandemic underlines the importance of strengthening IPAC expertise related to LTC homes and improving infection surveillance. Up-to-date and local expertise to guide response are important because recommendations considered best practice at one time point in the COVID-19 pandemic may not be appropriate for another time point. For example, LTC homes have seen fluctuations in infection and death rates over the course of the pandemic and with that, comes different guidance measures. The impact of the waves of the COVID-19 pandemic have been very different. High-quality and current data along with added expertise would improve our ability to ensure protection of residents while minimizing the collateral harms of outbreak prevention and control measures.

Importance of High Quality and Current Data

Many long-standing structural and systemic weaknesses in LTC homes were amplified and exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Having LTC home data during the COVID-19 pandemic has brought to light the vulnerabilities this population faces and demonstrates the impact of the different waves of COVID-19.

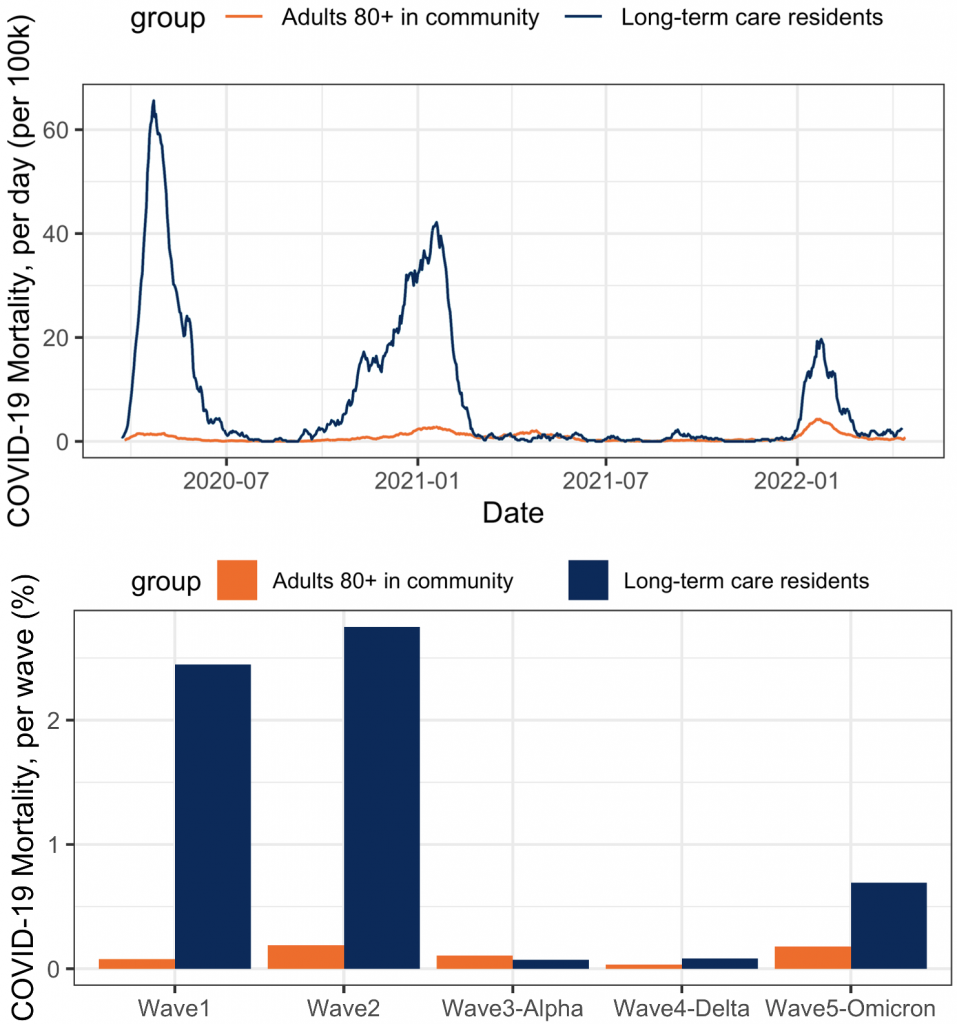

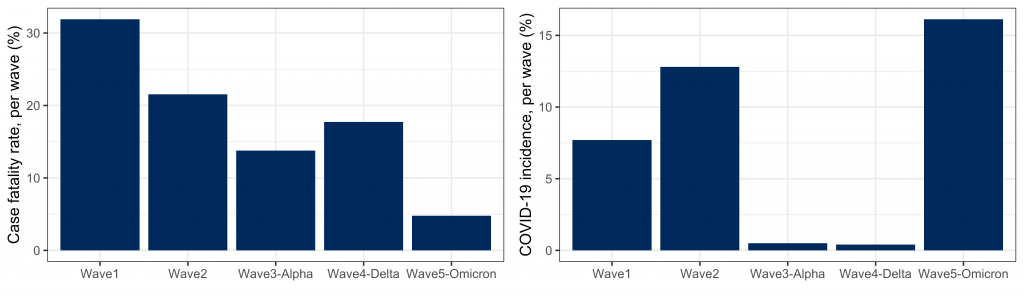

Waves were defined as: wave 1 (prior to August 1, 2020), wave 2 (August 1, 2020, to February 28, 2021), wave 3 (Alpha; March 1, 2021, to May 31, 2021), wave 4 (Delta; June 1, 2021, to November 30, 2021), wave 5 (Omicron; since December 1, 2021). Data provided by Public Health Ontario.

For example, the first and second waves of the pandemic had a disproportionate burden on LTC home residents (Figure 2); the incidence of COVID-19 specific mortality in LTC homes was 29.6 (95% confidence interval (CI): 22.5, 39.0) times that of adults 80 years of age and older living in the community in wave 1 and 13.5 (95%CI: 10.9, 16.7) times in wave 2. More than 2% of LTC home residents perished in each of wave 1 and wave 2. A rapid and timely vaccination campaign during the 3rd (Alpha) wave greatly mitigated the burden on LTC home residents during this wave. The Delta wave also had relatively little mortality impact on LTC home residents, largely due to vaccination. In the Omicron wave, there has been a return to higher COVID-19 attributable mortality in LTC homes compared to community-dwelling 80+ year old adults (rate ratio (RR)=3.7, 95%CI: 2.8, 4.9; see Figure 2). Being able to respond to the rapidly changing situation is made possible by having high-quality and current data.

The severity of COVID-19 cases, as measured by the case fatality rate, dropped over 6-fold from wave 1 (31.9%) to wave 5 (4.8%) (Figure 3). The case fatality rate in LTC homes, remains quite high during the Omicron wave and is substantially higher than influenza in Ontario LTC and retirement home residents pre-pandemic (3.5%).29 Therefore, the volume of SARS-CoV-2 cases in the Omicron wave (N = 11,466), means that the Omicron wave, once again, had a substantial burden on LTC home residents. These data highlight the vulnerability of LTC home residents, particularly in times of high community COVID-19 transmission.

Building on the lessons learned during this pandemic is critical to creating sustained and meaningful change. Policy and decision-makers can work towards improving the quality of care and optimizing data collection across the areas of focus is critical for the ongoing measurement of progress and success.

Waves were defined as: wave 1 (prior to August 1, 2020), wave 2 (August 1, 2020, to February 28, 2021), wave 3 (Alpha; March 1, 2021, to May 31, 2021), wave 4 (Delta; June 1, 2021, to November 30, 2021), wave 5 (Omicron; since December 1, 2021). Data provided by Public Health Ontario.

Interpretation

Lessons learned during the COVID-19 pandemic for LTC homes can be used as the guiding principle for driving sustained change. Care for LTC home residents needs to be reformed and reimagined with the core theme of care that is resident-centered and focused on providing the best quality of life possible for residents. In our review of Federal and Ontario reports that address the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in LTC homes, these are the five lessons learned.

First, enhance entry and retention of LTC home staff through the creation of more full-time positions, adequate staffing, and improvement of working conditions. Poor conditions of work have been a major factor making it difficult to recruit and retain LTC home staff. Addressing staffing issues is critical to the well-being and quality life of LTC home residents. Improvements and incentives provided to LTC home workers brought on by the urgent demands placed on the workforce by the COVID-19 pandemic were a short-term solution to a much larger systemic problem. Attaining and retaining the adequate number of skilled staff long-term requires making permanent the changes to pay introduced during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sustained improvements will require the creation of more full-time positions with reasonable pay and benefits, ensuring training for staff and ensuring staff autonomy within the home to respond to resident needs. Decreasing and avoiding the use of agency staff where possible will reduce mobility of staff between LTC homes and allow for better continuity and quality of care for residents. A system of tracking direct resident care hours and collecting verifiable data is necessary to ensure accountability and transparency. These staffing improvements are critical to ensuring that LTC homes meet the target of 4 hours of direct care calculated per resident.

Second, reduce crowding through the elimination of three and four-bed ward rooms and creation of more private rooms with dedicated bathrooms. Reducing crowding remains an important and under-recognized issue in LTC homes. The need to eliminate three and four bed ward rooms now, by capping the occupancy to a maximum of two residents per room in existing homes and building only private rooms with dedicated bathrooms in new builds can improve the well-being and quality of life of residents. In the COVID-19 pandemic, empty beds in ward rooms were left vacant to allow for a maximum of two residents in these rooms. Moving forward, these rooms should remain at a maximum capacity of two residents permanently. Any new beds created should be exclusively private rooms with dedicated bathrooms, unless there is an identified need (e.g., accommodation for couples) for some two-bed rooms. Ongoing data collection in LTC homes to monitor infection rates in relation to crowding and room occupancy can optimize resident safety. The design of new LTC homes further needs to take into consideration space to reduce the risk of transmission of infection and improve the quality of life for residents, staff, families and essential caregivers.

Third, maintain the ability for essential caregivers to have in-person access to the resident. The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the invaluable role essential caregivers and family members play in maintaining quality care. Maintaining connection and the ability for essential caregivers to enter LTC homes is imperative for the emotional health and well-being of the residents who have been deeply impacted by isolation associated with COVID-19 restrictions. The pandemic has also brought to light the wide range of assistance provided to residents and staff by family and friends, demonstrating as well, the need for new and innovative ways to connect residents with family members and essential caregivers (in person and virtually) to reduce loneliness and isolation. Providing residents with this connection is essential for their well-being and visits with essential caregivers and family members or alternative ways of connecting when visiting is not possible need to be prioritized.

Fourth, ensure residents have access to timely and high-quality palliative care that promotes both quality and length of life. Incorporating and strengthening a palliative care approach within LTC homes is an important component of providing well-rounded care for residents. Residents of LTC homes are frail and often have serious or life-limiting illnesses making conversations about goals of care and end of life important. Data are needed on the level and quality of palliative care being provided in LTC homes to identify areas for improvement. Whenever possible, LTC homes should strive to avoid transfers to the emergency room and hospital at the end-of-life and aim to provide the necessary care and comfort for the resident in the LTC home. Education, access to palliative care resources and where possible, pooled resources using a community of practice approach should be offered to the staff of LTC homes.

Fifth, build and maintain IPAC expertise within LTC homes. Resources to develop a robust program include a dedicated IPAC practitioner within each LTC home. Further, these experts need to be connected to external IPAC expertise and resources and as well to their local public health resources.

Finally, ongoing collection of timely and high-quality LTC home data is critical to ensure all five aims are achieved in ordered to reduce infections and deaths, and to improve the quality of care of residents of LTC.

Methods Used for This Science Brief

Evidence Scan

The COVID-19 Evidence Synthesis Network performed a research evidence scan for this Science Brief. The search was last updated on December 3, 2021. Key recommendations to improve LTC homes were summarized from reports obtained through a search of the literature, grey literature, and relevant websites. The areas that we focused on were staffing, crowding, and palliative care. Later, we included ensuring connections with essential caregivers and IPAC. These areas of focus were derived from a list of eight measures that could be effective in preventing COVID-19 outbreaks, hospitalization, and deaths in Ontario LTC homes published in an earlier pivotal Science Table report “COVID-19 and Ontario’s Long-Term Care Homes”.3 A search for literature on long term care homes, including grey literature was conducted using the terms “long-term care home” and “recommendations”, and followed this with one of the topics of interest (e.g., crowding, staffing etc.). The following synonyms for each topic of interest were used:

Crowding: “multi-bed rooms” and “single bed rooms”;

Staffing: “recruitment’, “retention”; and

Palliative care: “end of life care”.

The search was limited to the Canadian context and yielded five primary reports. Finally, we identified opportunities to strengthen these recommendations and to integrate them into Ontario policy by leveraging the expertise of the members of the Ontario COVID-19 Science Table Congregate Care Working Group, members of the Ontario COVID-19 Science Advisory Table and other experts in the field to identify relevant evidence.

Estimating Incidence of COVID-19 Cases and Mortality in LTC homes and Community

We identified COVID-19 cases and deaths, using data extracted from the Case and Contact Management system (CCM) on April 18, 2022. Deaths where SARS-CoV-2 was considered unrelated to cause of death (incidental), were excluded. We measured the incidence of deaths (deaths divided by population), as well as the incidence of SARS-CoV-2 cases (cases divided by population). The number of LTC home residents was estimated based on the Continuing Care Reporting System at the time of the beginning of each wave (wave 1: 77,547, wave 2: 70,456, wave 3: 65,507, wave 4: 70,015, wave 5: 71,123), and Ontario population 80 years of age and over was based on Statistics Canada Census data for the population 80 years of age and older in Ontario (659,648, in waves 1 & 2, 674,976, in waves 3, 4, & 5) minus the estimated population of LTC home residents in that wave that were 80 years of age and older (estimated to be 71%).30 Incidence rate ratios (comparing LTC home resident mortality rate versus the mortality rate of community residents 80 years of age and older) were estimated using negative binomial regression, and included 95% confidence intervals. The case fatality rate was also reported, defined as the number of deaths divided by the number of cases; for this analysis, cases that died but were considered unrelated to SARS-CoV-2 were excluded from both the numerator and the denominator. All analyses were conducted in R (version 4).

References

1. Innovation Government of Canada. Long-term care and COVID-19. Published 2020. https://www.ic.gc.ca/eic/site/063.nsf/eng/h_98049.html

2. Edvardsson D, Sandman PO, Nay R, Karlsson S. Dementia in long-term care: Policy changes and educational supports help spur a decrease in inappropriate use of antipsychotics and restraints. J Nurs Manag. 2009;17(1):59-65. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2834.2008.00891.x

3. Stall NM, Brown KA, Maltsev A, et al. COVID-19 and Ontario’s long-term care homes (full brief). Sci Briefs Ont COVID-19 Sci Advis Table. 2021;2(7). https://doi.org/10.47326/ocsat.2021.02.07.1.0

4. Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat. Population in long-term care facilities, 2016 Census. https://open.canada.ca/data/en/dataset/74528098-6f62-48fc-9a95-99bd287d2dab

5. Wong EKC, Thorne T, Estabrooks C, Straus SE. Recommendations from long-term care reports, commissions, and inquiries in Canada. F1000 Research. Published online February 10, 2021. https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.43282.1

6. Canadian Institute for Health Information. The impact of COVID-19 on long-term care in Canada: Focus on the first 6 months.; 2021:34. https://www.cihi.ca/sites/default/files/document/impact-covid-19-long-term-care-canada-first-6-months-report-en.pdf

7. Estabrooks CA, Straus SE, Flood CM, et al. Restoring trust: COVID-19 and the future of long-term care in Canada. FACETS. 2020;5(1):651-691. https://doi.org/10.1139/facets-2020-0056

8. National long-term care services standard. HSO Health Standards Organization. Published March 31, 2021. https://healthstandards.org/uncategorized/national-long-term-care-services-standard/

9. Marrocco FN, Coke A, Kitts J. Ontario’s long-term care COVID-19 commission: Final report. Published online 2021:426. http://www.ltccommission-commissionsld.ca/report/pdf/20210623_LTCC_AODA_EN.pdf

10. COVID-19 preparedness and management: Special report on management of health-related COVID-19 expenditures. Office of the Auditor General of Ontario; 2021:107. https://www.auditor.on.ca/en/content/specialreports/specialreports/COVID-19_ch5readinessresponseLTC_en202104.pdf

11. Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario (RNAO). Long-term care systemic failings: Two decades of staffing and funding recommendations.; 2020. https://rnao.ca/sites/rnao-ca/files/RNAO_LTC_System_Failings_June_2020_1.pdf

12. Harrington C, Swan JH. Nursing home staffing, turnover, and case mix. Sage J. Published online 2003. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077558703254692

13. Tombaugh M. Appropriateness of minimum nurse staffing ratios in nursing homes: Phase II final report.; 2001:12. https://theconsumervoice.org/uploads/files/issues/CMS-Staffing-Study-Phase-II.pdf

14. Long-Term Care Staffing Study Advisory Group. Long-term care staffing study. Ontario Ministry of Long-Term Care; 2020:51. https://files.ontario.ca/mltc-long-term-care-staffing-study-en-2020-07-31.pdf

15. Armstrong T. An act to amend the long-term care homes act, 2007 to establish a minimum standard of daily care. Legislative Assembly of Ontario; 2018:2. https://www.ola.org/sites/default/files/node-files/bill/document/pdf/2018/2018-08/b013_e.pdf

16. Patient protection and affordable care act of 2010. No. 111-148, 124 Stat.; 2010. https://www.congress.gov/111/plaws/publ148/PLAW-111publ148.pdf

17. Transition to payroll-based journal (PBJ) staffing measures on the nursing home compare tool on medicare.gov and the five star quality rating system. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; 2018. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Provider-Enrollment-and-Certification/SurveyCertificationGenInfo/Downloads/QSO18-17-NH.pdf

18. Fact sheet: Protecting seniors by improving safety and quality of care in the nation’s nursing homes. The White House. Published February 28, 2022. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/02/28/fact-sheet-protecting-seniors-and-people-with-disabilities-by-improving-safety-and-quality-of-care-in-the-nations-nursing-homes/

19. Brown KA, Jones A, Daneman N, et al. Association between nursing home crowding and COVID-19 infection and mortality in Ontario, Canada. medRxiv. Published online June 23, 2020:2020.06.23.20137729. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.23.20137729

20. Stall NM, Jones A, Brown KA, Rochon PA, Costa AP. For-profit long-term care homes and the risk of COVID-19 outbreaks and resident deaths. CMAJ. 2020;192(33):E946-E955. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.201197

21. Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. COVID-19 Directive #3 for long-term care homes under the long-term care homes act, 2007.; 2021:12. https://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/pro/programs/publichealth/coronavirus/docs/directives/LTCH_HPPA.pdf

22. Long-term care home design manual 2015. Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care; 2015:57. https://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/public/programs/ltc/docs/home_design_manual.pdf

23. National Institute on Ageing. The NIA’s recommended ‘titanium ring’ for protecting older Canadians in long-term care and congregate living settings. Published 2021. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5c2fa7b03917eed9b5a436d8/t/60f19e0b9f13d96b48e1d861/1626447381041/Titanium+Ring+-+July+16%2C+2021.pdf

24. Savage RD, Rochon PA, Na Y, et al. Excess mortality in long-term care residents with and without personal contact with family or friends during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2022;23(3). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2021.12.015

25. Tanuseputro P, Hsu A, Kuluski K, et al. Level of need, divertibility, and outcomes of newly admitted nursing home residents. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2017;18(7):616-623.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2017.02.008

26. Tanuseputro P, Chalifoux M, Bennett C, et al. Hospitalization and mortality rates in long-term care facilities: Does for-profit status matter? J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2015;16(10):874-883. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2015.06.004

27. Pallium Canada – advancing palliative care. Pallium Canada. https://www.pallium.ca/

28. Congregate Care Settings Working Group. Supporting long-term care home residents during Omicron. Ont COVID-19 Sci Advis Table. Published online February 10, 2022. https://covid19-sciencetable.ca/sciencebrief/supporting-long-term-care-home-residents-during-omicron/

29. Paphitis K, Achonu C, Callery S, et al. Beyond flu: Trends in respiratory infection outbreaks in Ontario healthcare settings from 2007 to 2017, and implications for non-influenza outbreak management. Can Commun Dis Rep. 2021;47(56):269-275. https://doi.org/10.14745/ccdr.v47i56a04

30. Government of Canada. Population estimates on July 1st, by age and sex. Statistics Canada. Published September 29, 2020. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1710000501

Document Information & Citation

Author Contributions: PAR conceived the Science Brief. PAR and JML wrote the first draft of the Science Brief. KAB performed the analyses. All authors revised the Science Brief critically for important intellectual content and approved the final version.

Citation: Rochon PA, Li JM, Johnstone J, et al. The COVID-19 pandemic’s impact on long-term care homes: Five lessons learned. Science Briefs of the Ontario COVID-19 Science Advisory Table. 2022;3(60). https://doi.org/10.47326/ocsat.2022.03.60.1.0

Author Affiliations: The affiliations of the members of the Ontario COVID-19 Science Advisory Table can be found at https://covid19-sciencetable.ca/.

Declarations of Interest: The declarations of interest of the members of the Ontario COVID-19 Science Advisory Table, its Working Groups, or its partners can be found at https://covid19-sciencetable.ca/. The declarations of interest of external authors can be found under Additional Resources.

Copyright: 2021 Ontario COVID-19 Science Advisory Table. This is an open access document distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that the original work is properly cited.

The views and findings expressed in this Science Brief are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of all of the members of the Ontario COVID-19 Science Advisory Table, its Working Groups, or its partners.