Key Message

Rates of opioid-related harms, particularly fatal overdose, have increased significantly in Ontario during the COVID-19 pandemic and have disproportionately impacted marginalized and racialized populations.

Strategies to address this crisis include ensuring uninterrupted and equitable access to addiction, mental health, and harm reduction services; incorporating these services into high-risk settings such as shelters, hotels, and encampments; adapting harm reduction services to meet current needs; and promoting access to alternative service delivery methods such as telemedicine programs when in-person services are not available.

Leveraging Ontario’s capacity to monitor rates of opioid-related harms can help optimize public health strategies. Data gaps on disparities for those disproportionately impacted by the opioid overdose crisis need to be addressed to improve our understanding of the effectiveness of interventions and guide implementation in high-risk populations.

Summary

Background

Rates of opioid-related harm, particularly fatal overdose, have increased significantly in Ontario during the COVID-19 pandemic. Reducing the burden of opioid-related harm among people who use drugs (PWUD) will require systematic interventions and ongoing evaluation of the effectiveness of these interventions.

Questions

How has the COVID-19 pandemic impacted opioid-related harm in Ontario?

What are the factors associated with increased rates of opioid-related harm during the COVID-19 pandemic?

How can Ontario reduce the burden of opioid-related harm for the remainder of the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond?

Findings

Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020, rates of emergency medical services (EMS) for suspected opioid overdose increased by 57% and rates of fatal opioid overdose increased by 60% in Ontario. Fentanyl, sedatives, and stimulants are also more commonly found in post-mortem toxicology reports of persons with fatal opioid overdoses, pointing to an increasingly volatile supply (unpredictable potency and composition) of unregulated opioids and other drugs. Rural and Northern communities, people experiencing poverty or homelessness, people experiencing incarceration, and Black, Indigenous, People of Colour (BIPOC) communities have seen largest relative increases.

Factors that may have contributed to rising rates of opioid-related harm during the COVID-19 pandemic include pandemic-related stress, social isolation, and mental illness, which in turn resulted in changes in drug use behaviours; border and travel restrictions that created a more erratic and volatile unregulated drug supply; and reduced accessibility of addiction, mental health, and harm reduction services. These factors intersect with and are compounded by pre-existing barriers to receiving adequate care among PWUD. Barriers include stigma surrounding drug use and systemic inequities associated with social determinants of health (SDOH) such as housing instability, gender, race, ethnicity, socio-economic status, disability status, sexual orientation.

Proposed strategies to address opioid-related harm during the COVID-19 pandemic include supporting continuity and access to addiction and harm reduction services, incorporating these services in high-risk settings, such as shelters and encampments, addressing the volatile drug supply through adaptive harm reduction strategies, improving access to telemedicine and remote care services, promoting COVID-19 vaccination and supporting the implementation of COVID-19 infection prevention protocols to increase safety of addiction treatment and harm reduction services. Based on expert commentary within the published literature, these strategies will only be effective when they include a comprehensive suite of services for both mental and physical health, provide culturally safe and trauma-informed care, address SDOH, and are tailored to the unique client needs by partnering with PWUD.

Interpretation

Ontario is facing increased rates of opioid-related harm alongside the public health emergency of the COVID-19 pandemic. Strategies to address opioid-related harm during COVID-19 include facilitating continuity and access to addiction and harm reduction services through use of telemedicine/virtual care and incorporating these services into high-risk settings, addressing the volatile drug supply through adaptive harm reduction strategies, promoting vaccination and supporting the use of COVID-19 safety protocols. The implementation of these strategies will require ongoing collaboration between PWUD, service providers, researchers, and government to ensure that they are implemented in a safe, equitable, and effective manner.

Full Text

Background

The opioid overdose crisis is a leading public health concern in Canada and refers to a rapid increase in rates of opioid-related harm, particularly fatal overdose, over the past two decades.1 Between 2016 and 2020, an estimated 6,819 people died from fatal opioid overdose in Ontario, accounting for 35% of the total number of deaths due to opioid overdose in Canada during that timeframe.2 The origin of this crisis is complex and multifaceted, involving both prescribed and unprescribed opioid use; however, the recent surge in accidental fatal overdoses is largely attributed to the emergence of unregulated fentanyl, a potent synthetic opioid, and its analogues in the drug supply.1,3

The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated the opioid overdose crisis and complicated the ongoing public health response by reducing social supports for PWUD, intensifying mental health challenges, and limiting access to addiction treatment and harm reduction services, including supervised consumption services, due to physical distancing and other measures to prevent the spread of COVID-19.4 Combined with the ongoing impact of COVID-19 on the health of Canadians, this has created a dual public health crisis and strategies to mitigate the increasing rates of opioid-related harm during the COVID-19 pandemic are urgently required.

Questions

How has the COVID-19 pandemic impacted opioid-related harm in Ontario?

What are the factors associated with increased rates of opioid-related harm during the COVID-19 pandemic?

How can Ontario reduce the burden of opioid-related harm for the remainder of the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond?

Findings

Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Opioid-Related Harm in Ontario

Table 1 presents most important indicators. Opioid-related harms are evaluated at the population-level by monitoring trends in opioid-related mortality, EMS responses for opioid overdose, opioid-related emergency department (ED) visits, and opioid-related hospitalizations.

| Indicator | Impact of COVID-19 pandemic |

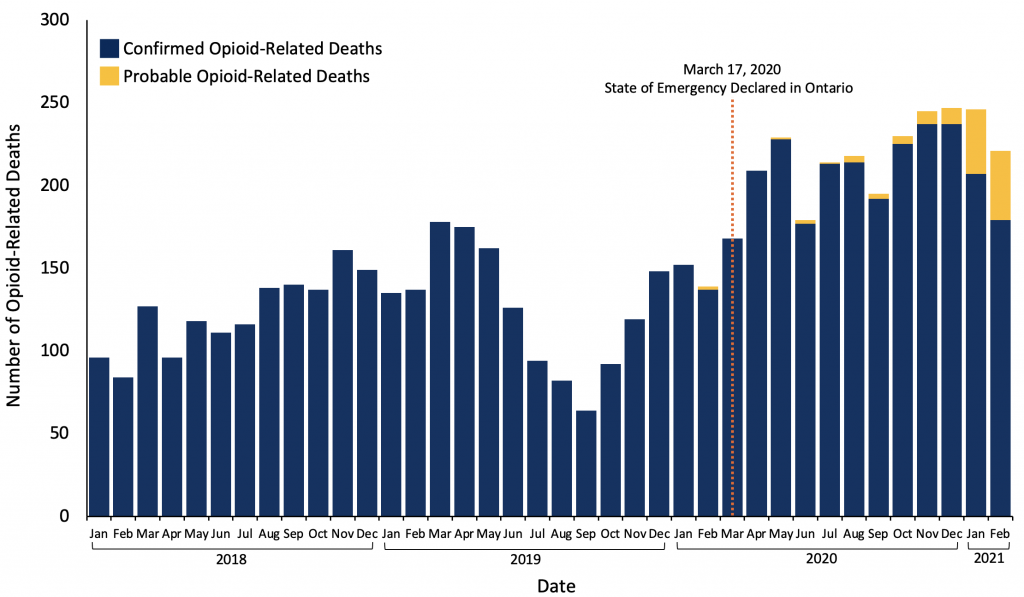

| Opioid-Related Mortality | The number of opioid-related deaths across Ontario significantly accelerated in the months following the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in Ontario (Figure 1). In 2020, there were 2,426 opioid-related deaths in Ontario, an increase of 60% and 64% from 1,517 deaths in 2019 and 1,475 opioid-related deaths in 2018, respectively.5 Preliminary data on total opioid-related deaths (confirmed and probable) for the first two months of 2021 show this upward trend is continuing, with 467 opioid-related deaths in January and February of 2021.6 This represents an increase of 60% compared to the number of opioid-related deaths in the same period in 2020 and a 71% increase compared to 2019. |

| Opioid-Related Emergency Medical Services (EMS) | From April-September 2020, there were 2,159 EMS responses for suspected opioid overdose in Ontario, an increase of 57% and 83% compared to the same period in 2019 (1,374 EMS responses) and 2018 (1,180 EMS responses), respectively.7 |

| Opioid-Related ED Visits | The number of opioid-related ED visits in Ontario between 2019 and 2020 did not increase, while opioid-related ED visits increased by 8% nationally.8 |

| Opioid-Related Hospitalizations | The number of opioid-related hospitalizations in Ontario increased by 2% between 2019 and 2020, with a 7% increase nationally.8 |

EMS, emergency medical services. ED, emergency department.

Multiple data sources for these indicators demonstrate a shift towards an increase in opioid-related harms during the COVID-19 pandemic, the most significant being a 60% increase in fatal opioid overdose in 2020 compared to 2019 (Figure 1).

Monthly number of opioid-related deaths in Ontario prior to, and during, the COVID-19 pandemic through to February 2021 based on data from 2018 to December 2019 from Public Health Ontario Interactive Opioid Tool (accessed on June 22, 2021), and opioid-related mortality data for January 2020 to February 2021, Office of the Chief Coroner for Ontario, extracted June 11, 2021.

Disproportionately Impacted Subgroups

Certain populations in Ontario have experienced disproportionate increases in opioid-related harm during the pandemic. These include:

- People living in rural and Northern communities5,9

- People who are unable to afford basic resources and services10

- People experiencing homelessness or housing instability5,11,12

- Men and individuals between the ages of 20-492,5

- Neighbourhoods with higher ethno-cultural diversity (based on data from Ontario)10 and, people in BIPOC communities (based on international data)13,14

- People experiencing incarceration or who have been recently released from prison4,5,12

These priority groups require specific attention when considering public health measures aimed at addressing increased rates of opioid-related harm during COVID-19; however, this is not an exhaustive list.4,12 It is vital to consider the intersection between these and other SDOH, such as stigma surrounding drug use and other structural barriers to receiving adequate healthcare, when evaluating and addressing the sociodemographic disparities in opioid-related harm that have emerged during the COVID-19 pandemic.12,15

Characteristics of Fatal Opioid Overdoses

Compared to the pre-pandemic period, fatal opioid overdoses in Ontario during the COVID-19 pandemic were more likely to:5

- Occur outdoors or in temporary emergency shelter settings (i.e., hotels/motels/inns and shelters), although not all of these trends were statistically significant

- Involve smoking or inhalation, as opposed to injection, as the route of opioid use

- Involve the synthetic opioid fentanyl based on post-mortem toxicology

- Involve stimulants such as cocaine and methamphetamine based on post-mortem toxicology

- Involve benzodiazepines not approved for therapeutic use (e.g., etizolam, flualprazolam, flubromazolam) based on post-mortem toxicology

- Be accidental, although overall, most confirmed opioid-related deaths in Ontario are accidental in nature (92.6% of opioid-related deaths were accidental pre-pandemic versus 95.7% during the pandemic)

Factors Associated with Increased Rates of Opioid-Related Harm during the COVID-19 Pandemic

In addition to the impact of elevated mental and physical stress during the pandemic (e.g., fear of contracting COVID-19 illness, financial strain due to loss of employment), other factors specific to the pandemic that may contribute to opioid-related mortality include the impacts of restrictive public health measures on PWUD (Table 2) and disruptions in health and harm reduction services for PWUD.

| Factor | Impact on Opioid Crisis |

| Physical Distancing and Isolation | Social isolation increases the likelihood of using opioids alone and reduces ability to safely access drugs, leading to increased periods of abstinence, or to increased stockpiling behaviour to prevent periods of abstinence.4,16 Although physical distancing may reduce the likelihood of bystander intervention to respond to fatal overdoses, there was no difference in the percentage of opioid-related deaths in Ontario that occurred when no one was present to intervene during the pandemic (72.6%) versus pre-pandemic (73.1%).5 |

| Border and Travel Restrictions | Border and travel restrictions can create a more erratic and volatile drug supply by disrupting unregulated drug supply chains. The volatile drug supply mainly refers to the unregulated opioid supply that is primarily composed of fentanyl; however, other substances (particularly non-prescription benzodiazepines such as etizolam) are also increasingly found in the unregulated opioid supply during the COVID-19 pandemic.17,18 The volatility of the drug supply has the potential to increase the risk of fatal overdoses due to changes in patterns of use and tolerance to opioids as well as unintended exposures to adulterants.4 |

| Stress and Worsening Mental Health | The COVID-19 pandemic, combined with the necessary public health measures used to combat it, has contributed to increasing stress and worsening mental health among Canadians.19 This may contribute to increased use of substances – including both regulated substances, like alcohol and cannabis, as well as unregulated substances.20 |

PWUD, people who use drugs.

Disruptions in Health and Harm Reduction Services for People Who Use Drugs

In the first month of the pandemic, new registrations for specialized addiction services in Ontario dropped by 70% and waitlist times increased due to reduced capacity.21 In-person harm reduction services, including supervised consumption services, have also experienced disruptions, such as having to reduce hours or capacity to accommodate COVID-19 safety protocols, in contrast to a significant increase in virtual care visits (Table 3).21 Opioid Agonist Therapy (OAT) services were also initially disrupted;21 however, rapid changes to the delivery of OAT, including relaxed clinical guidelines surrounding OAT prescription, were immediately implemented in Ontario to facilitate continuity of OAT services.

| Factor | Impact |

| Reduced Capacity in Harm Reduction Services | Harm reduction services provide equipment and education to reduce the risks associated with drug use (e.g., provision of sterile injection or safer smoking equipment, supervised injection services, etc.) and facilitate access to health and social services.21 Reduced access to these services may lead to disruption in access to healthcare services and/or increase the risk of overdose. |

| Disruption of Opioid Agonist Therapy (OAT) | OAT is an evidence-based pharmacologic therapy to treat opioid use disorder and is effective in reducing opioid-related harm, including fatal overdose.22 Disruption of OAT provision during the COVID-19 pandemic may lead to an increased use of opioids from the unregulated drug supply and overdose among individuals with opioid use disorder.23 Ontario has minimized OAT disruption during COVID-19 by modifying clinical guidelines and OAT regulations during COVID-19 (discussed in the following section). |

OAT, Opioid Agonist Therapy.

Strategies to Reduce the Burden of Opioid-Related Harm during the COVID-19 Pandemic

Many evidence-based public health strategies are used to reduce opioid-related harm and were in place prior to COVID-19. Broadly speaking these can be divided into primary prevention efforts, treatments for opioid use disorder, including OAT, and harm reduction services.24

Primary Prevention:

Primary prevention includes the promotion of safer opioid prescribing practices among healthcare workers and educational initiatives to promote safer drug use in both the general population and subgroups at a high risk of opioid-related harm.24

Treatment for Opioid Use Disorder:

This includes OAT and specialized addiction services (group therapy, counselling, etc.). OAT is the use of evidence-based, prescribed pharmacological treatments for opioid use disorder, and is effective in reducing opioid-related harm, including fatal overdose.22 Medications used for OAT include methadone, buprenorphine-naloxone, and slow-release oral morphine, which are prescribed by a licensed medical practitioner.

Harm Reduction Services:

Harm reduction services reduce the harms associated with drug use through measures such as:24

- Providing equipment for safer drug use (e.g., distribution of sterile injection equipment and safer smoking and inhalation equipment)

- Supervised spaces to use drugs (supervised consumption services)

- Prescribing a safer supply of opioids to reduce the risk of harm associated with the increasingly volatile unregulated opioid supply

- Access to naloxone kits to reduce the risk of overdose mortality

As described above, many of these services have been disrupted during the COVID-19 pandemic. These disruptions were compounded by barriers to accessing these services that existed prior to the pandemic, including stigma surrounding drug use, geographic disparities in service availability (i.e., rural and Northern settings), and underlying SDOH that impact access to healthcare services, such as poverty, residential instability, and homelessness. These barriers will continue to impact morbidity and mortality from substance use unless they are addressed during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond. Further, these services are most effective when they are combined with a holistic suite of health and social services provided in a culturally safe and trauma-informed care environment, address SDOH such as housing instability, and are tailored to the unique needs of the local population by incorporating input from PWUD.13,15,25–27

Based on review of the literature, the following four strategies are proposed as part of an integrated system of care to address rising rates of fatal opioid overdoses during the COVID-19 pandemic:

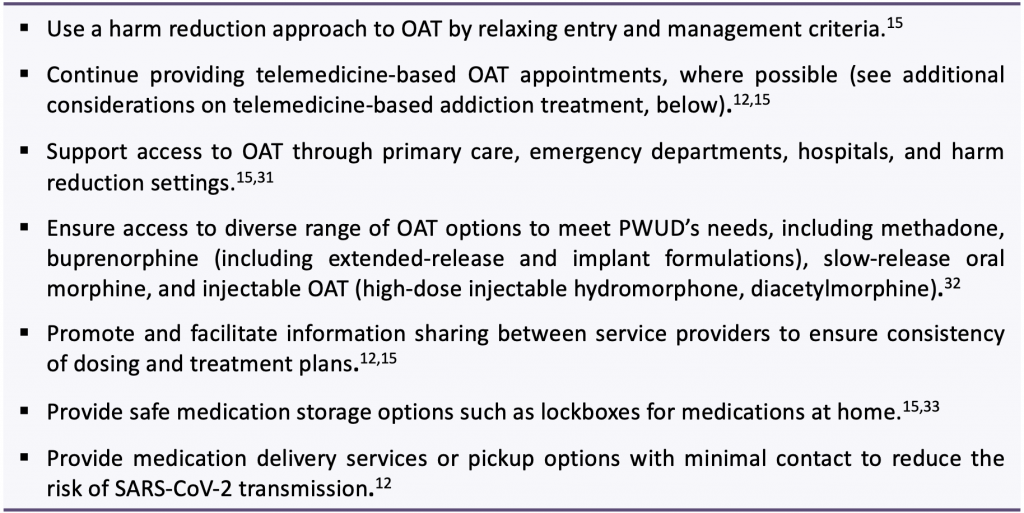

Ensure Opioid Agonist Therapy (OAT) Access, Options, and Continuity

OAT is an effective and life-saving treatment for opioid use disorder.22 Interruptions to OAT increase the risk of relapse and overdose; therefore, ensuring uninterrupted and equitable access to OAT is imperative to minimize opioid harms during COVID-19.

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, clinical guidelines surrounding the provision of OAT were relaxed to facilitate treatment continuity during pandemic restrictions.28 For example, prescribers were given increased discretion to provide extended take-home supplies (‘carries’) of OAT medications and permitted to prescribe OAT over the phone.29These measures improved OAT continuity and, despite initial concerns of sharing or improper dosing of OAT medications, there is no evidence that they increased the risk of harm to patients or communities.30

OAT, Opioid Agonist Therapy. PWUD, people who use drugs.

It is also important to note that changes in federal and provincial prisons during COVID-19, such as temporary or early release of select individuals to reduce overcrowding, have disrupted OAT continuity for many people who were released from prison and were receiving OAT in the corrections system.4,5 This population is already at an elevated risk of opioid overdose; therefore, facilitating OAT continuity among people who have recently been incarcerated should be prioritized.

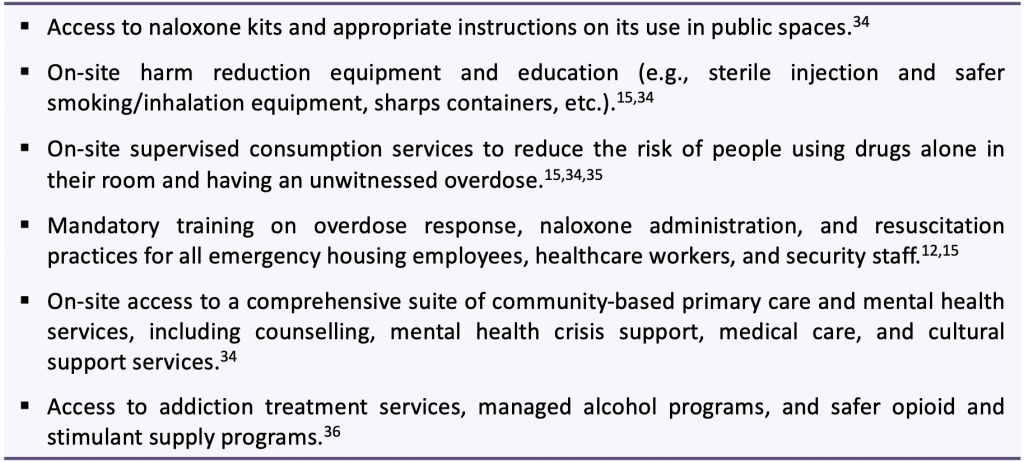

Incorporate Harm Reduction Services and Access to Healthcare Services into All Supportive Housing and Shelter Settings Where Many Fatal Opioid Overdoses Are Occurring

Many PWUD do not access OAT and other treatments due to barriers in accessing healthcare and social services adapted to their needs. During the pandemic, increases in fatal opioid-related overdose have been documented outdoors, in shelters, respite and emergency shelter settings (e.g., hotels being used as COVID-19 physical-distancing and isolation sites), and among people experiencing housing instability or homelessness.5 These spaces represent centralized locations to provide access to harm reduction and healthcare services.

Increasing the accessibility of harm reduction and low threshold healthcare services (including addiction treatment services) by administering them in locations being used to provide shelter and temporary emergency housing for people experiencing homelessness or who are self-isolating because of COVID-19 can help to address the healthcare needs of these populations during the pandemic and may continue to be impactful beyond the pandemic. Community outreach services can increase engagement and decrease barriers to access. These types of integrated services are being developed and implemented in Ontario.

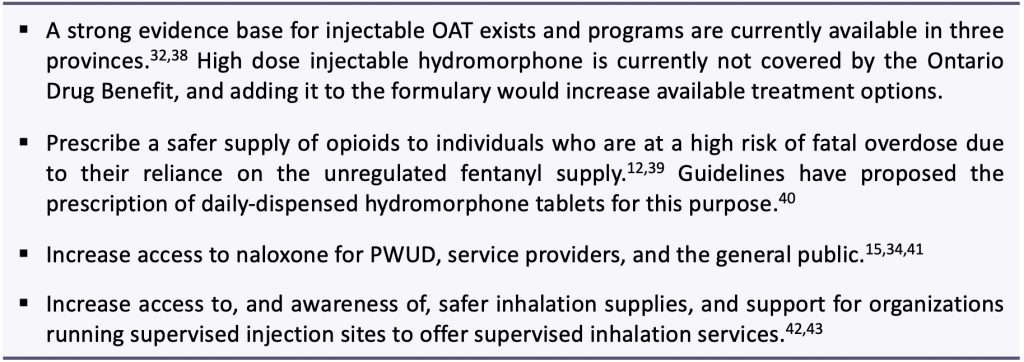

Facilitate Adaptive Harm Reduction Strategies

An increasing proportion of fatal opioid overdoses involve fentanyl, concurrent exposure to sedatives and stimulants, and inhalation as the route of opioid use.5 These changes should be reflected in the approach to harm reduction.

There is evidence that changes and potential disruptions to the drug supply chain during COVID-19 are contributing to volatility in the unregulated drug supply.17 These changes may impact PWUD in several ways including reduced tolerance due to an inability to access opioids or using unregulated fentanyl that also contains non-prescription benzodiazepines.29,37

OAT, opioid agonist therapy. PWUD, people who use drugs.

Consideration for all the above strategies should be given in locations and communities which have been identified as having a higher risk of fatal opioid overdoses to increasing availability and awareness of harm reduction strategies.

Ensure That Care for Persons Who Use Drugs Remains Accessible, While Minimizing Risk of Exposure to SARS-COV-2 for Patients and Providers

Telemedicine:

Addiction treatment and harm reduction services have become less accessible during the COVID-19 pandemic. Telemedicine strategies are an approach for service delivery when in-person care is unavailable.44

Many mental health and addiction providers have pivoted to provide services via web-based video chat platforms (such as Zoom, Webex, and the Ontario Telehealth Network), telephone, synchronous chat platforms, and text messaging.21While these telemedicine solutions can improve the accessibility of addiction treatment and harm reduction services they can also create health inequities due to disparities in access to technology, the internet, or because of inadequate privacy controls.45,46 Community outreach services can increase engagement and decrease barriers to access.47

Integrate COVID-19 Safety Protocols, Training, Resources into Addiction and Harm Reduction Services:

Many essential in-person addiction treatment and harm reduction services continue to operate during the pandemic. PWUD are at a disproportionately high risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection and severe COVID-19 illness.48 To ensure that these services operate safely and to minimize the risk of closure or reduced capacity, support must be provided to staff and clients to ensure that COVID-19 safety protocols can be adhered to in these settings.

PWUD, people who use drugs. PPE, personal protective equipment.

Interpretation

Rates of opioid-related harm, particularly fatal overdose, have increased significantly during the COVID-19 pandemic. Considerable efforts have been made amongst front-line service providers in Ontario to attenuate the increase in rates of fatal overdose and other opioid-related harms in vulnerable populations prior to, and during, the COVID-19 pandemic. This brief presents an overview of the problem and strategies that can be used to minimize the risk of opioid-related harm during the COVID-19 pandemic. Many of these strategies, including less restrictive OAT regulations, increasing access to harm reduction services and other health services within shelters and temporary emergency shelter settings, addressing stigma in the healthcare system and dealing with upstream SDOH will also be helpful for addressing overdose mortality beyond the pandemic.

Access to addiction treatment and harm reduction services (such as supervised consumption services) is not uniform across the Province of Ontario. Some of the communities with the highest rate of overdose death in the province (e.g., rural communities) do not have access to the strategies or interventions outlined above. Demographic subgroups that have been disproportionately impacted by opioid-related harm during the COVID-19 pandemic include rural and Northern communities, people experiencing poverty or homelessness, people experiencing incarceration, and BIPOC communities.

The effectiveness of the strategies proposed in this brief can be assessed and iteratively adapted in an ongoing fashion by monitoring indicators of opioid harm. However, there remain gaps in provincial data capabilities related to the measurement of disparities for populations who are disproportionately impacted by the opioid crisis, such as those from racialized or other marginalized communities. Efforts to collect rates of opioid-related harms for specific subgroups, through ongoing investment in the Ontario opioid data infrastructure and collaboration with community stakeholders and individuals with lived experience, are required to examine the effectiveness of interventions in these populations. Provincial efforts should also interface and attempt to align with Federal policy and the work of the Expert Task Force on Substance Use in a manner that best supports PWUD.

Addressing the overdose crisis will depend on a coordinated effort amongst PWUD, service providers, researchers, and government that prioritizes harm reduction during a time of disruption and ensures that service providers are adequately supported to assist their clientele (i.e., with operating finances, adequate space, supplies, personnel, etc.). Success will also depend on tailoring strategies to meet local needs and adequately addressing barriers to care in disproportionately impacted populations through new and ongoing investments. Attention to addressing the SDOH, particularly the impact of homelessness and lack of long-term affordable housing, is required to reduce the harms of the overdose crisis. Ongoing discussion with local stakeholders and PWUD will ensure that the rapid increase in fatal opioid overdose during the COVID-19 pandemic is addressed in a safe, equitable, and effective manner. Further, collaborating with, and supporting, the organizations that have been leading efforts to reduce rates of opioid-related harm in Ontario is essential, as they have first-hand knowledge of the strategies that work for the populations they serve.

Methods Used for This Science Brief

Opioid-related mortality data from the Office of the Chief Coroner for Ontario from January 2018 to December 2019 were downloaded from Interactive Opioid Tool, accessed on June 22, 2021. Opioid-related mortality data for January 2020 to February 2021 were obtained from the Office of the Chief Coroner for Ontario, extracted June 11 2021. Information on characteristics of opioid-related mortality in Ontario were obtained from reports issued by Ontario Drug Policy Research Network (2020) and Public Health Ontario (2021). Data on other opioid-related harms (use of EMS services, ED visits, hospitalizations) were obtained from reports published by the Canadian Institute for Health Information (2021) and Public Health Agency of Canada (2021).

In addition, we searched PubMed, Google Scholar, the COVID-19 Rapid Evidence Reviews, the Joanna Briggs Institute’s COVID-19 Special Collection, LitCovid in PubMed, and grey literature sources using the guidelines outlines by the University of Toronto Libraries for articles related to opioid use, opioid-related harm, and public health strategies to address the opioid overdose crisis during the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition, we retrieved reports citing relevant articles through Google Scholar and reviewed references from identified articles for additional studies.

References

1. Public Health Agency of Canada. Evidence synthesis – The opioid crisis in Canada: a national perspective. Published May 9, 2018. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/reports-publications/health-promotion-chronic-disease-prevention-canada-research-policy-practice/vol-38-no-6-2018/evidence-synthesis-opioid-crisis-canada-national-perspective.html

2. Public Health Agency of Canada. Apparent opioid and stimulant toxicity deaths: Surveillance of opioid- and stimulant-related harms in Canada, January 2016 to December 2020.; 2021. https://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2021/aspc-phac/HP33-3-2020-eng-3.pdf

3. Gomes T, Juurlink DN. Opioid use and overdose: What we’ve learned in Ontario. Healthc Q. 2016;18(4). https://doi.org/10.12927/hcq.2016.24568

4. Nguyen T, Buxton JA. Pathways between COVID-19 public health responses and increasing overdose risks: A rapid review and conceptual framework. Int J Drug Policy. 2021;93:103236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2021.103236

5. Gomes T, Murray R, Kolla G, et al. Changing circumstances surrounding opioid-related deaths in Ontario during the COVID-19 pandemic.; 2021. https://odprn.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Changing-Circumstances-Surrounding-Opioid-Related-Deaths.pdf

6. Canadian Institute for Health Information. Unintended consequences of COVID-19: Impact on harms caused by substance use. Canadian Institute for Health Information; 2021:20. https://www.cihi.ca/sites/default/files/document/unintended-consequences-covid-19-substance-use-report-en.pdf

7. Public Health Agency of Canada. Suspected opioid-related overdoses based on emergency medical services: Surveillance of opioid- and stimulant-related harms in Canada, January 2017 to September 2020.; 2021. https://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2021/aspc-phac/HP33-5-2020-eng-2.pdf

8. Public Health Agency of Canada. Suspected opioid-related overdoses based on emergency medical services: Surveillance of opioid- and stimulant-related harms in Canada, January 2017 to June 2020.; 2020. https://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2021/aspc-phac/HP33-5-2020-eng-1.pdf

9. Morin KA, Acharya S, Eibl JK, Marsh DC. Evidence of increased fentanyl use during the COVID-19 pandemic among opioid agonist treatment patients in Ontario, Canada. Int J Drug Policy. 2021;90:103088. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2020.103088

10. The Ontario Drug Policy Research Network, The Office of the Chief Coroner for Ontario/Ontario Forensic Pathology Service, Public Health Ontario, Centre on Drug Policy Evaluation. Preliminary patterns in circumstances surrounding opioid-related deaths in Ontario during the COVID-19 pandemic. Published online November 2020:24. https://odprn.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Opioid-Death-Report_FINAL-2020NOV09.pdf

11. Perri M, Dosani N, Hwang SW. COVID-19 and people experiencing homelessness: Challenges and mitigation strategies. CMAJ. 2020;192(26). https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.200834

12. Henderson R, McInnes A, Mackey L, et al. Opioid use disorder treatment disruptions during the COVID-19 pandemic and other disasters: A scoping review addressing dual public health emergencies. Published online September 7, 2021. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-244863/v1

13. Wendt DC, Marsan S, Parker D, et al. Commentary on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on opioid use disorder treatment among Indigenous communities in the United States and Canada. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2021;121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2020.108165

14. Ochalek TA, Cumpston KL, Wills BK, Gal TS, Moeller FG. Nonfatal opioid overdoses at an urban emergency department during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA. 2020;324(16):1673-1674. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.17477

15. Public Health Ontario. Rapid Review: Strategies to mitigate risk of substance use-related harms during periods of disruption.; 2020:41. https://www.publichealthontario.ca/-/media/documents/ncov/he/2020/09/mitigation-strategies-substance-use.pdf?la=en

16. Stack E, Leichtling G, Larsen JE, et al. The impacts of COVID-19 on mental health, substance use, and overdose concerns of People Who Use Drugs in rural communities. J Addict Med. Published online September 2, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1097/ADM.0000000000000770

17. Canadian Community Epidemiology Network on Drug Use. CCENDU Alert: Changes related to COVID-19 in the illegal drug supply and access to services, and resulting health harms.; 2020. https://www.ccsa.ca/sites/default/files/2020-05/CCSA-COVID-19-CCENDU-Illegal-Drug-Supply-Alert-2020-en.pdf

18. Government of British Columbia. Illicit drug toxicity deaths in BC, January 1, 2011 to June 30, 2021. Coroners Service; 2021. https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/birth-adoption-death-marriage-and-divorce/deaths/coroners-service/statistical/illicit-drug.pdf

19. Enns A, Pinto A, Venugopal J, et al. Substance use and related harms in the context of COVID-19: a conceptual model. Published September 14, 2020. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/reports-publications/health-promotion-chronic-disease-prevention-canada-research-policy-practice/vol-40-no-11-12-2020/substance-use-related-harms-covid-19-conceptual-model.html

20. Rotermann M. Canadians who report lower self-perceived mental health during the COVID-19 Pandemic more likely to report increased use of cannabis, alcohol and tobacco.; 2020. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/45-28-0001/2020001/article/00008-eng.htm

21. Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction. Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on substance use treatment capacity in Canada.; 2020:8. https://www.ccsa.ca/sites/default/files/2020-12/CCSA-COVID-19-Impacts-Pandemic-Substance-Use-Treatment-Capacity-Canada-2020-en.pdf

22. Eibl JK, Morin K, Leinonen E, Marsh DC. The state of opioid agonist therapy in Canada 20 years after federal oversight. Can J Psychiatry. 2017;62(7). https://doi.org/10.1177/0706743717711167

23. Dunlop A, Lokuge B, Masters D, et al. Challenges in maintaining treatment services for people who use drugs during the COVID-19 pandemic. Harm Reduct J. Published online 2020. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-020-00370-7

24. Hawk KF, Vaca FE, D’Onofrio G. Reducing fatal opioid overdose: Prevention, treatment and harm reduction strategies. Yale J Biol Med. 2015;88(3). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4553643/

25. Strike C, Watson TM. Losing the uphill battle? Emergent harm reduction interventions and barriers during the opioid overdose crisis in Canada. Int J Drug Policy. 2019;71:178-182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2019.02.005

26. Smye V, Browne AJ, Varcoe C, Josewski V. Harm reduction, methadone maintenance treatment and the root causes of health and social inequities: An intersectional lens in the Canadian context. Harm Reduct J. 2011;8(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7517-8-17

27. Pauly BB, Reist D, Belle-Isle L, Schactman C. Housing and harm reduction: what is the role of harm reduction in addressing homelessness? Int J Drug Policy. 2013;24(4):284-290. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2013.03.008

28. Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. COVID-19 opioid agonist treatment guidance.; 2020. http://metaphi.ca/assets/documents/news/COVID19_OpioidAgonistTreatmentGuidance.pdf

29. Russell C, Ali F, Nafeh F, Rehm J, LeBlanc S, Elton-Marshall T. Identifying the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on service access for people who use drugs (PWUD): A national qualitative study. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2021;129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2021.108374

30. Figgatt MC, Salazar Z, Day E, Vincent L, Dasgupta N. Take-home dosing experiences among persons receiving methadone maintenance treatment during COVID-19. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2021;123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2021.108276

31. Hu T, Snider-Adler M, Nijmeh L, Pyle A. Buprenorphine/naloxone induction in a Canadian emergency department with rapid access to community-based addictions providers. Can J Emerg Med. 2019;21(4):492-498. https://doi.org/10.1017/cem.2019.24

32. Public Health Ontario. Evidence Brief: Effectiveness of Supervised injectable Opioid Agonist Treatment (SiOAT) for Opioid Use Disorder.; 2017. https://www.publichealthontario.ca/-/media/documents/E/2017/eb-effectiveness-sioat.pdf?la=en

33. Kidorf M, Brooner RK, Dunn KE, Peirce JM. Use of an electronic pillbox to increase number of methadone take-home doses during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2021;126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2021.108328

34. Dong K, Meador K, Hyshka E, et al. Supporting people who use substances in acute care settings during the COVID-19 pandemic: CRISM – Interim Guidance Document.; 2021. https://crism.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Supporting-people-who-use-substances-in-acute-care-settings-during-the-COVID-19-pandemic-V2-18-Feb-2021.pdf

35. Willson M, Phillips R, Jensen K, et al. Infrastructure for harm reduction in residential and hotel settings. Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research; 2020. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5eb1a664ccf4c7037e8c1d72/t/60ef3cd27042580ad1e64558/1626291508038/infrastructure+for+harm+reduction+in+residential+and+hotel+settings.pdf

36. Pauly B (Bernie), Vallance K, Wettlaufer A, et al. Community managed alcohol programs in Canada: Overview of key dimensions and implementation. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2018;37(S1). https://doi.org/10.1111/dar.12681

37. Ali F, Russell C, Nafeh F, Rehm J, LeBlanc S, Elton-Marshall T. Changes in substance supply and use characteristics among people who use drugs (PWUD) during the COVID-19 global pandemic: A national qualitative assessment in Canada. Int J Drug Policy. 2021;93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2021.103237

38. Fairbairn N, Ross J, Trew M, et al. Injectable opioid agonist treatment for opioid use disorder: a national clinical guideline. CMAJ. 2019;191(38):E1049-E1056. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.190344

39. Tyndall M. Safer opioid distribution in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Drug Policy. 2020;83:102880. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2020.102880

40. Ahamad K, Bach P, Brar R, et al. Risk mitigation in the context of dual public health emergencies. British Columbia Centre on Substance Use; 2020. https://www.bccsu.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Risk-Mitigation-in-the-Context-of-Dual-Public-Health-Emergencies-v1.5.pdf

41. Antoniou T, McCormack D, Campbell T, et al. Geographic variation in the provision of naloxone by pharmacies in Ontario, Canada: A population-based small area variation analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2020;216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108238

42. Bourque S, Pijl EM, Mason E, Manning J, Motz T. Supervised inhalation is an important part of supervised consumption services. Can J Public Health. 2019;110(2). https://doi.org/10.17269/s41997-019-00180-w

43. Foreman-Mackey A, Bayoumi AM, Miskovic M, Kolla G, Strike C. ‘It’s our safe sanctuary’: Experiences of using an unsanctioned overdose prevention site in Toronto, Ontario. Int J Drug Policy. 2019;73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2019.09.019

44. Barsom EZ, Feenstra TM, Bemelman WA, Bonjer JH, Schijven MP. Coping with COVID-19: scaling up virtual care to standard practice. Nat Med. 2020;26(5). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-020-0845-0

45. Strudwick G, Sockalingam S, Kassam I, et al. Digital interventions to support population mental health in Canada during the COVID-19 pandemic: Rapid review. JMIR Ment Health. 2021;8(3). https://doi.org/10.2196/26550

46. Bruneau J, Rehm J, Wild TC, et al. Telemedicine support for addiction services: National Rapid Guidance Document.; 2020. https://crism.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/CRISM-National-Rapid-Guidance-Telemedicine-V1.pdf

47. Olivet J, Bassuk EL, Elstad E, Kenney R, Shapiro L. Assessing the evidence: What we know about outreach and engagement. Homeless Hub. Published 2009. https://www.homelesshub.ca/resource/assessing-evidence-what-we-know-about-outreach-and-engagement

48. Wang QQ, Kaelber DC, Xu R, Volkow ND. COVID-19 risk and outcomes in patients with substance use disorders: analyses from electronic health records in the United States. Mol Psychiatry. 2021;26(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-020-00880-7

49. Ministry of Health. COVID-19 Guidance: Consumption and Treatment Services (CTS) Sites. Government of Ontario; 2020. https://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/pro/programs/publichealth/coronavirus/docs/2019_consumption_treatment_services_guidance.pdf

50. Khorasheh T, Kolla G, Kenny K, Bayoumi A. Impacts of Overdose: Evaluating the effects of grief and loss from overdose on people who inject drugs and developing an intervention to address them.; 2021. https://maphealth.ca/wp-content/uploads/Bayoumi_HRW_BriefReport.pdf

Document Information & Citation

Author Contributions: PK, EF, ET, LZ, CM, and LM conceived the Science Brief. EF, ET, LZ, and PK wrote the first draft of the Science Brief. All authors revised the Science Brief critically for important intellectual content and approved the final version.

Citation: Friesen EL, Kurdyak PA, Gomes T, et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on opioid-related harm in Ontario. Science Briefs of the Ontario COVID-19 Science Advisory Table. 2021;2(42). https://doi.org/10.47326/ocsat.2021.02.42.1.0

Author Affiliations: The affiliations of the members of the Ontario COVID-19 Science Advisory Table can be found at https://covid19-sciencetable.ca/.

Declarations of Interest: The declarations of interest of the members of the Ontario COVID-19 Science Advisory Table, its Working Groups, or its partners can be found at https://covid19-sciencetable.ca/. The declarations of interest of external authors can be found under Additional Resources.

Copyright: 2021 Ontario COVID-19 Science Advisory Table. This is an open access document distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that the original work is properly cited.

The views and findings expressed in this Science Brief are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of all of the members of the Ontario COVID-19 Science Advisory Table, its Working Groups, or its partners.